2. Listen and Look

Listen to the podcast by historian Dan Snow called The Irish Border with Professor Marie Coleman. They talk about why Ireland has a border and many of the causes of the Irish War of Independence.

Listen to the podcast by historian Dan Snow called The Irish Border with Professor Marie Coleman. They talk about why Ireland has a border and many of the causes of the Irish War of Independence.

Click on the image or on this link: https://play.acast.com/s/dansnowshistoryhit/theirishborderwithprofessormariecoleman

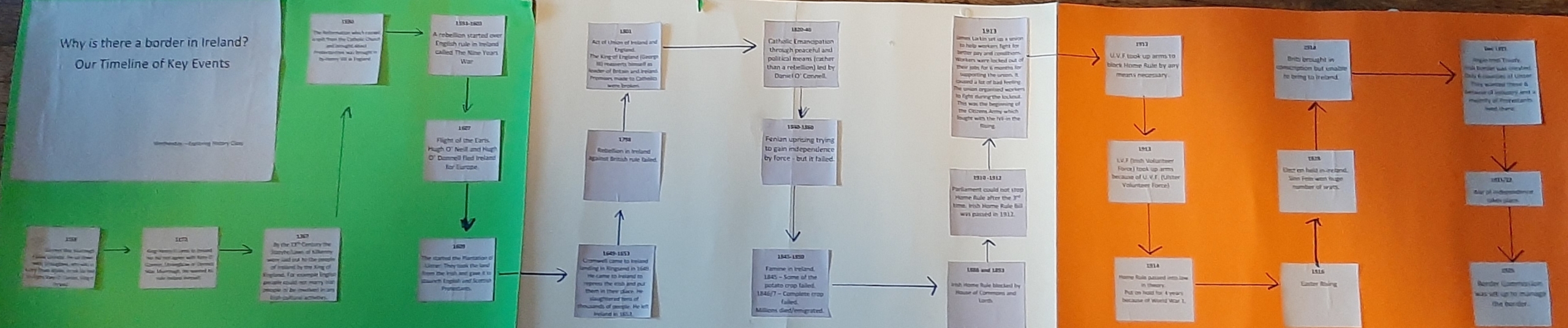

Look at the timeline that our own Exploring History students Paul Gibbons, Rita O’ Neill, Rose Swan, Linda Leavey and Angela Cross, created having listened to this podcast in 2019.

Look at the timeline that our own Exploring History students Paul Gibbons, Rita O’ Neill, Rose Swan, Linda Leavey and Angela Cross, created having listened to this podcast in 2019.

Click the link here to see it in detail – https://www.preceden.com/timelines/662250-woi

3. Read

3. Read

Read the following article written by Shane O’ Brien for www.irishcentral.com titled: How the 1916 Easter Rising gave way to Ireland’s War of Independence.

How the 1916 Easter Rising gave way to Ireland’s War of Independence

By Shane O’ Brien

For many, the differences between the three-year Irish War of Independence and the 1916 Easter Rising become blurred.

The conflict between British forces and Irish volunteers escalated in earnest in 1920 and the centenaries of several key moments in Ireland’s bid for freedom will be marked in 2020.

However, the Irish War of Independence and Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising often get blurred together with the passage of time. It’s important to make the distinction between two different, but related, Irish revolutions because, to those who didn’t grow up with an education in Irish history, the difference between the ill-fated Easter Rising and the successful War of Independence can get a little confusing.

The close proximity of the two revolutions, coupled with the fact that many of the leaders of Ireland’s bid for freedom also fought on Easter week in 1916, means that the two conflicts are synonymous with one another.

But there were almost three years between the last shots of the Rising in Dublin and the first shots of the War of Independence in Soloheadbeg, Tipperary.

It is important, therefore, to look at the two conflicts as two separate events where the Rising had a significant bearing on what came next, rather than viewing them as two entirely separate conflicts or one continuous war.

On the face of it, they are almost polar opposites of one another.

The 1916 Rising was borne out of Britain’s ongoing war with Germany and the opportunities that it presented, among other things.

The rebels were overwhelmingly vilified by the Irish public who looked on, viewed them as responsible for the destruction of Dublin City and the deaths of hundreds of innocent civilians.

During the War of Independence, on the other hand, Irish rebels had almost complete support from the Irish people. Many rebels were sheltered by civilians in safe houses across the country in their fight against the Black and Tans, the Royal Irish Constabulary [RIC] and other occupying forces.

That seismic shift in public sentiment can be largely, but not exclusively, attributed to the events directly after the Easter Rising, when British authorities made the fatal decision to execute the leaders of the upstart without trial.

The executions of James Connolly, who was so badly wounded he was a shot in a chair, and Joseph Mary Plunkett, who was married on the eve of his execution, were particularly harsh and whipped the Irish public into a frenzy.

To paraphrase W.B. Yeats, one of Ireland’s greatest poets, the political landscape in Ireland was “changed, changed utterly.”

A terrible beauty was born.

Other events, like the plan to introduce conscription in Ireland in 1918, helped to deepen the divide between the Irish people and the British Government, but the execution and martyring of 1916’s leaders turn public opinion irreversibly and gave Ireland an unstoppable momentum towards achieving its independence.

It was this dual-blunder of the 1916 executions and the introduction of conscription in 1918 that gave rise to Sinn Féin’s popularity.

In the 1918 British general election, Sinn Féin would win 73 seats out of 105 available on the island of Ireland – a staggering feat considering they were only founded a year previously.

Sinn Féin vowed to fight for an independent Ireland, showing that the people of Ireland overwhelmingly rejected British rule in Ireland.

In a tradition that continues to this day, Sinn Féin did not take their seats in the British parliament in Westminster but instead set up Dáil Éireann in January 1919.

This would give the Irish rebels something that their counterparts in 1916 did not have; a political wing that could be sent to negotiate when the time came.

Coincidentally, the first shots of the War of Independence were fired on the same day that the Dáil sat for its first session.

So, with the will of the people and an elected government behind them, Ireland’s latest band of rebels had more hope than ever before of winning independence from the United Kingdom.

That is another key difference between the Easter Rising and the War of Independence. The leaders of the 1916 Rising knew they would be defeated and knew they would likely meet their ends, but they carried on regardless in the hope their efforts would inspire others.

And that is exactly what transpired.

Soldiers during the 1916 Rising, like Michael Collins, rose to prominence during the War of Independence. They had been interned in Prisoner of War camps as retribution for their part in the Rising, but were released to appease the growing discord among the Irish public.

This partially accounts for the lengthy gap between the Rising’s end and the War of Independence’s beginning.

Collins himself was interned in Frongock Prison Camp in Wales and it was there that he began to think about different forms of warfare to hurt the superior British forces.

While the 1916 Rising was a grandiose act of war designed to attract the attention of the world, the War of Independence was a series of gritty skirmishes with few, if any, instances of a traditional battle.

Collins organized his troops into ‘flying columns’, comprised of between 20 and 100 men. The idea was to employ hit and run tactics on small targets like RIC barracks or British intelligence officers and then disappear into large crowds.

It was this guerrilla warfare that levelled the playing field between the inferior Irish forces and the vast expanses of the British Empire and 1920 saw an escalation in that warfare.

From Black and Tans to British spies and from the original Bloody Sunday to IRA ambushes, 1920 saw some of the most significant moments in recent Irish history.